Trump’s Tariffs To Test Resilience of U.S. West Coast Ports

By Jock O’Connell

An overwhelming majority of the nation’s leading economic analysts all across the political spectrum are at odds with President Trump’s proclivity for imposing tariffs on goods imported from America’s major trading partners.

The conservative Hoover Institution holds that President Trump’s tariffs represent “a misguided and harmful public policy…which will dampen economic activity in the United States and abroad, push up product prices for US consumers, and do little to achieve national security objectives”. The editorial board of the Wall Street Journal has excoriated the president for launching the “dumbest trade war in history”. Meanwhile, the liberal Nobel Prize laureate Paul Krugman has warned that “Trump’s tariff plan could rewind economic progress 90 years and ignite global conflict.”

So where does this leave America’s West Coast seaports?

The good news is that things could certainly be worse, at least in the near term.

The bulk of America’s $1.6 trillion merchandise trade with Canada and Mexico moves overland by truck, rail, and pipeline. Last year, only 9.7% of America’s entire merchandise trade with Mexico was transported by ship, while our waterborne trade with Canada was only 5.0% of total bilateral trade. Petroleum shipments alone accounted for 57.2% of America’s waterborne trade with Mexico and Canada last year.

As for containerized trade with our North American neighbors, USWC ports handled just $44 million of America’s $791 billion in merchandise trade with Canada last year. Similarly, container traffic with Mexico through USWC ports in 2024 was valued at $692 million of the total $834 billion in bilateral trade.

The president has also imposed tariffs on imports of certain industrial commodities, most prominently steel, aluminum, copper, and lumber. As the following four exhibits show, USWC ports do not play a substantial role in the inbound trade in these goods.

Last year, according to data collected by Customs and Border Protection, ports in the states of California, Oregon, and Washington accounted for just 12.1% of the 23,632,880 metric tons of steel and iron imported through U.S. ports. The 1,794,252 MT imported through the Ports of Los Angeles and Long Beach represented 7.6% share of U.S. trade, while the 481,350 MT handled by the Ports of Tacoma and Seattle gave the Northwest Seaport Alliance a 2.0% share. The 77,142 metric tons of steel and iron imported through the container-centric Port of Oakland in 2024 was actually exceeded by shipments into three of the West’s river ports: the Ports of Kalama (257,255 MT) and Vancouver (94,492 MT) on the Washington State side of the Columbia River and California’s Port of Stockton (107,142 MT) on the San Joaquin River.

The U.S. sources about two-thirds of its primary aluminum and 60 percent of scrap aluminum imports from Canada. The bulk of that trade is conducted overland. USWC ports held a 24.9% share of America’s waterborne imports of aluminum last year. Still, Canada is the largest source of U.S. aluminum imports, accounting for 41.4% of the $27.442 billion imported last year. Second place China’s share was 10.5%. Mexico’s share was 6.7%. Overall, though, America’s imports of aluminum have not been growing.

As Exhibit B shows, USWC ports last year handled a not insignificant 921,588 metric tons of aluminum imports. China accounted for 38.2% of the trade, with South Korea supplying 20.6% of the total. The Ports of Los Angeles and Long Beach dominated the trade with a combined 71.0% share of aluminum import tonnage through USWC ports. The Northwest Seaport Alliance accounted for a 14.7% share of aluminum imports through USWC ports, while the Port of Oakland’s share was 9.1%.

Most recently, in a move clearly intended to further penalize Canada, currently Mr. Trump’s Least Favored Nation, the White House has included softwood lumber in its target list for enhanced tariffs. Last year, 72.1% of all U.S. softwood lumber imports came from north of the border, with Germany (7.1%), Sweden (3.8%), and Brazil (3.1%) picking up slivers of the trade. Only a very small share of the softwood lumber import trade involves USWC ports, with the Port of Oakland accounting for the USWC’s largest share at 2.8% of all U.S. waterborne softwood lumber imports.

That’s about it for the it-could-be-worse news. For USWC ports, the biggest threat to business comes from the tariffs Mr. Trump is imposing on goods imported from China, the retaliatory tariffs Beijing is imposing on American products, and the billions of dollars in fees the President proposes to charge on Chinese-built ships calling at U.S. ports.

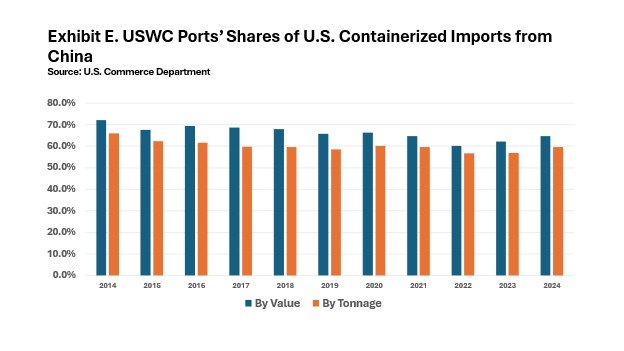

Exhibits E and F display the shares of U.S. waterborne trade with China that passes through USWC ports.

To be sure, not all of USWC-China seaborne trade is at risk from retaliatory tariffs. But China has singled out agricultural products both because U.S. farming communities tend to heavily favor Trump and because exporters in countries like Brazil and Argentina are available to fulfill much of China’s needs for imported soybeans, cereals, and grains.

Looking just at America’s soybean exports to China, Exhibit H shows the volumes passing through USWC ports.

It’s not only the megaports that are on the front lines of the trade conflict with China. While the top two ports for handling U.S. soybean exports to China are located in Louisiana near the mouth of the Mississippi River, seven of the next eight are on the West Coast. Last year, the Columbia River Ports of Portland, Kalama, Longview, and Vancouver collectively exported 7,583,977 metric tons of soybeans worldwide, 96.6% of which went to China. More generally, shipments to China accounted for 26.4% of all exports from these four smaller USWC ports.

In many ways, the most disruptive of the trade measures the Trump administration is proposing involves the huge fees that would be charged on Chinese-built ships calling at American ports.

Estimates of the portion of the world’s container shipping fleet built at Chinese shipyards range as high as 80%, meaning that U.S. exporters as well as importers would most likely incur additional transport costs should the fee be imposed. Trade in commodities with low profit margins would be jeopardized, a prospect that has prompted vigorous objections from farm exporters. As the Agricultural Transportation Coalition warned: “The transport cost increase would quickly render US ag unaffordable and uncompetitive, and because there is ample substitute supply from other countries, it would end US ag sales to foreign markets.”

But higher transport costs are not the least of the potential consequences of the fee. Shipping lines would almost predictably respond by curtailing service to all but the largest U.S. maritime gateways. That could dash Oregon’s aspirations of restoring regular container service at the Port of Portland’s Terminal 6 and could stymie the Port of Oakland’s hopes of attracting first-call service. It would, though, likely ensure that the volume of trade handled by the Ports of Los Angeles and Long Beach would rise and thus potentially result in costly congestion.

Less certain would be the fate of shipping through the Ports of Tacoma and Seattle, where shipping could be diverted to the Port of Vancouver or even to the under-utilized Port of Prince Rupert in British Columbia. Similarly, shipping could be rerouted to Mexico’s Pacific Coast ports, where the Ports of Manzanillo and Lazaro Cardenas are already handling increasing volumes of North America’s eastbound transpacific trade.

So, as exhilarating as it may be to “Move Fast and Break Things”, there are consequences.

The commentary, views, and opinions expressed by Jock O’Connell are his own and do not reflect the views or positions of the Pacific Merchant Shipping Association. PMSA does not endorse, support, or make any representations regarding the content provided by any third party commentator.