Supplying the Café Nervosa: How We Stay Caffeinated

By Jock O’Connell

Shortly after the cliff-hanging conclusion of a highly entertaining episode of Apple TV’s “Slow Horses”, a video clip (I’m told it’s called a trailer although it’s more like a preview) popped up on my iPad. It showed a segment of the once popular television series “Frasier” that featured an amusing interaction between Frasier Crane and his brother Niles as they were ordering outrageously complicated concoctions from an exasperated barista at Seattle’s fictional Café Nervosa.

I had a soupçon (as Frasier might say) of empathy for the preposterously pretentious Brothers Crane. After all, I had grown up on breakfasts of freshly percolated coffee and corn flakes before hurrying off each morning to grammar school. Further, during a junior year spent at the University of Vienna, I routinely found refuge from the winter cold in local coffee houses.

Back then, with certain exceptions, there was little to recommend the coffee Americans were drinking. Most folks did not meet friends for coffee but rather gulped a cup in the morning and otherwise sipped the swill dispensed in cafeteria urns. The best-selling coffees came in 16-ounce cans of ground beans sold by Chock Full o’ Nuts, Maxwell House, and Chase & Sanborn. None measured up to European, let alone Brazilian standards. De-caffeinated Sanka was considered an exotic beverage, drunk, to my knowledge, only by my dyspeptic Aunt Euphrasia.

There were some places around the country that defied the sorry national norm. New Orleans was one. Seattle was another. The former was the port through which much of America’s supply of green, unroasted coffee beans arrived from South and Central America. Innovative roasting, often involving chicory, was a long tradition in the Big Easy.

Seattle had been famous for its coffee culture well before it foisted Starbucks on the world. By some accounts, the Emerald City’s first commercial coffee bean roaster was founded in 1887. But what proved to be the real breakthrough in broadcasting Seattle’s cred as a coffee mecca came in 1908, when William and Edward Manning moved to town from Boston and opened Manning’s Coffee in the newly opened Pike Place Market. The Mannings were not content with dominating the local coffee scene. They began opening new shops throughout Washington State. By the 1920s, they were aggressively promoting Seattle coffee up and down the West Coast.

So, I wondered, how does the famously caffeinated population of Seattle get its coffee?

Except for coffee beans grown on 7,000 acres in Hawaii, all of the beans commercially roasted in this country come from abroad. According to the U.S. Department of Agriculture, the United States is the world’s second leading importer of coffee. In 2023, over 80% of U.S. unroasted coffee imports came from Latin America, principally from Brazil (23.1%) and Colombia (22.7%).

I poured through several histories of coffee consumption in the U.S. as well as the available government statistics on coffee imports into the United States (I won’t use the slavishly overused term “deep dive” to describe what I was up to).

My sifting through the information at hand led to several discoveries, the first of which was rather embarrassing. That Breville Barista Express counter-top espresso machine in which I had invested several hundred dollars a decade ago to slake my thirst for double espressos was not of French or even a Swiss origin. Breville, it turns out, is actually an Australian company that has been in business since 1932 and is headquartered in suburban Sydney. Not surprisingly, it’s machines are mostly manufactured in China. So, while I have no intention of throwing the machine away, I no longer say “merci” when it dispenses a cup.

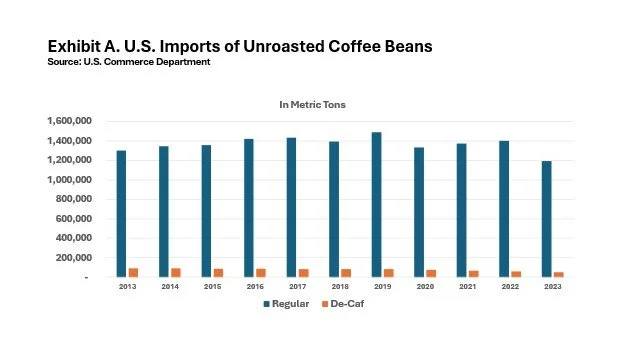

Exhibit A helpfully displays another surprising discovery. U.S. imports of unroasted coffee beans actually peaked in 2019 before dipping predictably in the first year of the pandemic when restaurants and coffee shops were mostly shuttered. The recovery of the import trade over the next couple of years can be partly attributed to the gradual easing of social distancing rules that permitted coffee houses to reopen, and the nation’s legion of professional baristas to once again perform their eye rolls and sneers on actual customers rather than on their unemployed roommates.

But the pandemic era rise in coffee bean imports can also be credited to surging imports of expensive espresso machines from Italy (up 85% between 2019 and 2022) as well as the soaring imports of the more rudimentary coffeemaking devices sold by firms like Nespresso and Keurig which are now found in most homes, hotel rooms, and Airbnbs, almost everywhere it seems other than psychiatrists’ waiting rooms.

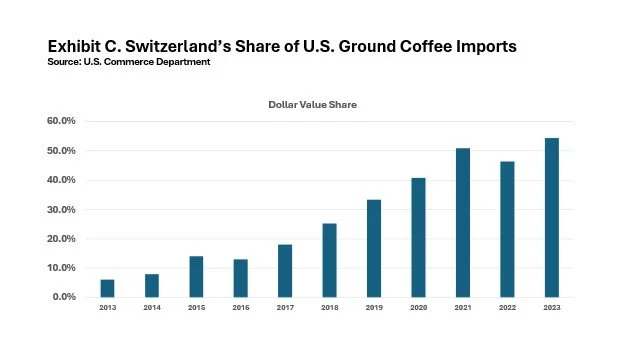

A third discovery involved the circular pods of ground coffee used in these espresso devices. Although nearly all of these contraptions are manufactured in Asia, the pods they use are mostly filled in Europe. Nespresso, which pioneered these devices, has three pod-filling facilities in Switzerland. So wouldn’t you know that, with the explosive growth of home-brewed espresso, three of the top five sources of imported roasted ground coffee into the United States are European, with Switzerland dominating the trade. See Exhibit B.

Exhibit C further attests to the impact of Nespresso and its competitors in reshaping trade in ground, roasted coffee.

A fourth finding was that – contrary to what I expected to find -- imports of unroasted coffee beans through the Northwest Seaport Alliance Ports of Tacoma and Seattle have been declining precipitously. See Exhibit D. Since topping out in 2017, coffee bean imports through the NWSA ports have fallen by 48.1% through last year.

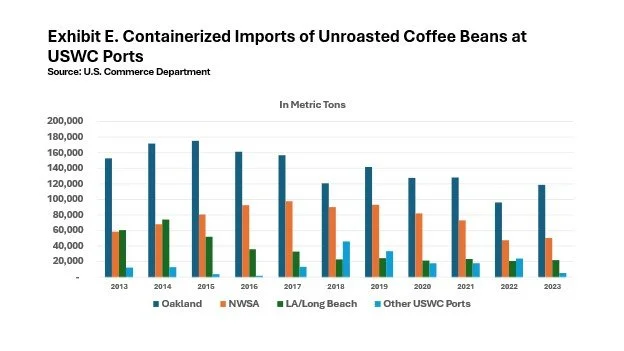

Further disconcerting, at least perhaps to Seattle’s civic boosters, is that the Ports of Seattle and Tacoma are not the principal West Coast ports of entry for unroasted coffee beans. That distinction goes to the Port of Oakland, as Exhibit E attests.

This shouldn’t be entirely surprising. The Port of Oakland serves a much larger market than do the NWSA ports. More to the point, the San Francisco Bay Area has a well-established affinity for coffee. The only surprising thing is that Oakland imports more coffee beans than the ports serving the very much larger Los Angeles metropolitan area. Chalk that up to a long history of how the coffee business in Central America came to channel coffee bean shipments to San Francisco’s roasters and distributors.

It’s just not that San Francisco routinely vies for the title of America’s most caffeinated city. Coffee has been part of San Francisco’s culture since the Gold Rush drew an enterprising young man – a 14-year-old boy, actually – from Nantucket who eschewed the gold fields of the Sierra for the emporiums springing up along the streets of San Francisco. His name was James Edgar Folger, and by 1859 he was the proprietor of the Pioneer Steam Coffee and Spice Mill. Like the Mannings in Seattle, young Folger was not content to remain a local purveyor of coffee beans or even the ground coffee beans gaining popularity with miners. He had broader aspirations which in time would make Folger’s a national brand.

San Francisco’s role as a hub of America’s coffee trade was further boosted by the arrival in 1873 of Austin and Reuben Hill, brothers from Rockland, Maine. They came from a family of successful shipbuilders and, like many who had experienced one winter too many in the Pine Tree State, sought a warmer, more congenial climate. In relatively short order they opened a grocery, purchased a coffee roaster, and established themselves formally as Hills Bros.

Meanwhile, the southward expansion of the Mannings coffee empire ultimately prompted the firm to move its administrative offices to San Francisco, along with its main coffee-roasting plant. By the turn of the century, the presence of major coffee merchants in San Francisco cemented its status as the chief West Coast port of entry for shipments of green, unroasted coffee beans from Latin America. By then, trading companies like the one founded by James Otis and James McAllister came along to handle the logistics of much of the city’s burgeoning trade in coffee beans. The firm they formed, Otis McAllister, is still active today in the comestible trade.

Through the years, the Port of San Francisco ceded its role as the primary Northern California seaport to the Port of Oakland, which has remained the West Coast’s principal gateway for unroasted coffee beans. Of the five plants Starbucks operates in the U.S. that roast, package, and distribute the company’s various brands and blends, including those sold under Costco’s Kirkland label, one is located a truck-ride from Oakland in Carson Valley, Nevada.

By the latter half of the 20th century, the San Francisco Bay Area became host to yet another billion-dollar coffee enterprise, the specialty coffee roaster Alfred Peet established in Berkeley in 1966. Contrary to the model set by previous West Coast coffee moguls, Peet did not hail from New England. He was Dutch. But his small batch coffees tapped into a hitherto underappreciated market for higher quality brews. Peet’s coffee beans are now largely imported through the Port of Oakland and are roasted in nearby Alameda before being packaged and distributed nationally. As for the late Mr. Peet, he is commonly recognized the “godfather” of the craft coffee movement in the United States…or its le parrain, as Frasier might say.

The commentary, views, and opinions expressed by Jock O’Connell are his own and do not reflect the views or positions of the Pacific Merchant Shipping Association. PMSA does not endorse, support, or make any representations regarding the content provided by any third party commentator.