California’s Wine Exports Bulk Up

By Jock O’Connell

It used to be that you couldn’t easily find a quality California wine in Europe. Often, you couldn’t find any California wine at all.

Back in 1975, when I was an underfed graduate student at the London School of Economics, I was invited to Thanksgiving dinner at an American couple’s home on the edge of Hampstead Heath. As they were also from California, I thought a bottle of Napa wine might be an apt contribution to what promised to be a grand feast.

So on that long ago Thanksgiving Day morning I set out for the grocery shop in Selfridge’s, the celebrated department store a few blocks south of where I was living at the top of Baker Street. Certainly, I assured myself, an emporium founded by an American (Harry Gordon Selfridge) would have at least one suitable California wine in stock. Nope. There was an ample supply of wines from France, Spain, and Italy as well as a tidy selection of ports from Portugal. But nothing at all from California.

Not to be discouraged, I then pressed on into the depths of Piccadilly, headed for Fortnum & Mason, the famed purveyors of fine foods and beverages to Her Majesty the Queen. But evidently no wine from the Golden State was yet deemed sufficiently fine for the royal palette.

With some desperation, I next strode over to Knightsbridge in the fading hope that Harrod’s, the retailer which pretty much defines luxury, might have a bottle of California wine in its cavernous and well-appointed food hall. No such luck.

But I did make off with an enormous apple pie. “It’s the last one,” the clerk remarked. “We baked four dozen today just for you Yanks.” And that’s how I came to be the third invitee at that Thanksgiving dinner who showed up with an apple pie from Harrod’s…but no wine.

I should point out that all of this preceded by several months the “Judgment of Paris”, the May 1976 blind tasting in the French capital that shocked European oenophiles when California wines bested the best the French had brought to the table.

Prior to that, California winemaking lacked international wineshop cred. In 1975, there were only 330 wineries in the entire state, nearly all of them family-run businesses without the wherewithal to market their products beyond their own excruciatingly utilitarian tasting rooms.

It was, indeed, a different world. More or less.

Today, California wines are readily available around the world, providing you know where to look and aren’t terribly discriminating about where the wine was actually bottled.

According to the Wine Institute of California, there are now 5,900 winegrape growers and 6,200 bonded wineries in a state that makes 85% of all U.S. wine and accounts for 95% of the nation’s wine exports. The Institute reports that California wineries export to 142 countries. Still, the customers tend to be concentrated, as Exhibit A makes obvious. (The markets listed account for over 80% of the state’s wine exports.)

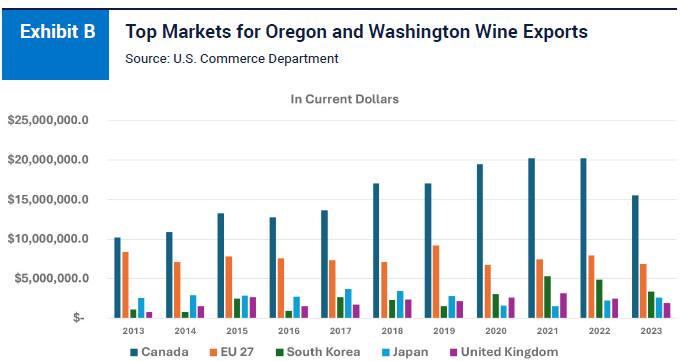

U.S. Commerce Department trade data presented in Exhibit B reveal a similar pattern of market concentration for wines being shipped from Oregon and Washington.

But how does all that this wine get from here to there?

If the shipments are bound for Canada (or Mexico, a small but fast-growing market for California wines), cases of wine will almost entirely be transported by truck or rail. For all other markets, the trade moves by sea.

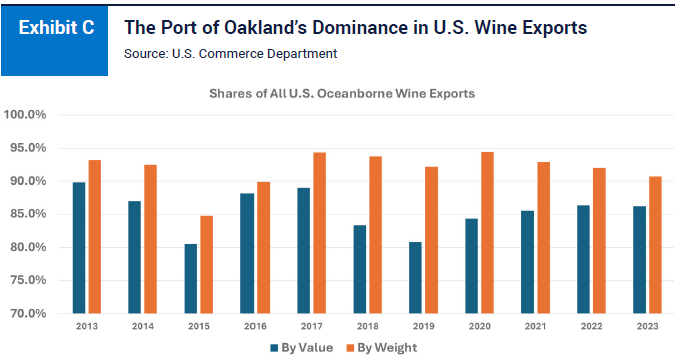

Given the geography of wine production in California, it should surprise no one that the Port of Oakland dominates the wine export trade, as Exhibit C demonstrates.

That answers part of the question about the logistics of shipping California wine around the globe. But there’s more to the question.

Most casual drinkers may think of wine being loaded aboard oceangoing freighters on palettes bearing cases containing a dozen 750-milliters glass bottles. And, certainly, that represents an ample share of the trade, especially when premium wines are involved. But more experienced imbibers might also be aware that wine is also transported in steel tanks or rubberized bladders that may hold over 24,000 liters or as much wine as would fill 32,000 standard wine bottles.

Even the most sophisticated wine connoisseurs may be surprised by just how much of California’s wine export trade involves bulk, as opposed to bottled, shipments.

While virtually all of the wine exported from California (and Oregon and Washington) to Canada is shipped overland in conventional glass bottles, that’s not true of California’s wine exports to the European Union and especially to the United Kingdom. See Exhibit D and Exhibit E for the percentages by weight and by value of California wine bulk exports to the state’s Top Five overseas markets.

From a logistical perspective, no overseas market for California wine is more peculiar than the United Kingdom. The trade has shifted dramatically – both in weight (Exhibit F) and by value (Exhibit G) - in recent years from wines shipped in conventional 750-millilter bottles to wines transported in bulk. The commodity breakdown in these two exhibits includes sparkling wines (which would lose their sparkle in a large shipping bladder) and a category I’ve labeled “Boxed?”. While the relevant HS code was originally intended to encompass magnums, jeroboams, and other outsized bottles up to 10 liters, it now includes those three-liter boxed wines that have been exploding in popularity.

To be sure, premium wines, especially those trading on terroir in Napa or Sonoma still travel exclusively in glass. Selfridge’s will now sell me a bottle of Opus One for £550 (about $700). Less extravagantly, Fortnum’s currently offers a £42 pinot noir from Failla Wines in St. Helena that would nicely complement turkey and stuffing. Much cheaper is the Apothic zinfandel from Modesto that’s currently been marked down by grocery chain Sainsbury to £12.50.

However, for mass market wines priced under $10, long-distance transportation costs quickly erode profits. A survey of the shelves in wine shops and grocery store chains in London or Paris turns up mostly wines selling for less than $15 or the local currency equivalent. The Monoprix near the Paris apartment we rented for the month of April featured scores of French, Spanish, and Italian wines at attractive, single-digit prices. There were even two California products, a Barefoot merlot and a red blend from Carnivor. If you didn’t know better, you might not realize that both brands are owned by Gallo. Indeed, the Modesto-based company is said to account for half of all California wine exports.

Once bulk wines are delivered to a port like Bristol, they go to a local bottler. The U.K. boasts a number of contract bottlers like Encirc Ltd. in Elton (Cheshire), Greencroft Bottling Company in Durham, and The Park in Bristol. Greencroft reports that it is building a new facility that can package some 28% of all wine sold in the U.K. Bottling wine from somewhere else is a huge business in the U.K. By one widely cited estimate, wineries in the U.K. produce fewer than ten million bottles of wine a year in a country that consumes 600 million bottles of wine annually.

For a consumer, what you’re getting may be hard to discern. Yes, it is a wine produced in California. Prominently featuring the state’s name on the label is the big selling point. Beyond that, though, labels can be an exercise in opacity.

Sainsbury’s is one of the leading grocers in the U.K. Its online catalog lists a pinot noir from Bread & Butter Wines in Napa that’s marked down this month to £13.50 from £15. The product notes state that the wine was “produced and bottled” by Bread & Butter. Sainsbury also offers its Sainsbury California Zinfandel 2019 for just £9. But here the product notes observe that the contents were “produced in the U.S. and bottled in the U.K.” The catalog further features five wines from Barefoot and four from Dark Horse. Miraculously, all sell for the identical price of price £10. All, it turns out, are Gallo products made from California grapes but bottled at the same facility in Uxbridge, England.

Tesco is the largest grocery chain in the U.K. Its wine offerings feature at least a half-dozen California wines under labels controlled by Gallo. Only one, a Gallo Family Vineyards merlot, makes that parentage clear. For the most part, these are wines produced in California and shipped to the U.K. in bulk for bottling.

In addition to the instore offerings, scores of businesses advertise on the internet that they can quickly supply British and European households with genuine California wines. One that caught my eye is a Czech firm that goes by the immodest name of CalifornianWines. It purports to represent over 130 California wineries, several of which are very respectable producers like Opus One, Daou Vineyards, Stag’s Leap, Rombauer Vineyards, Cakebread Cellars, and Robert Mondavi Winery.

I can’t vouch for the company. It says it uses DHL to ship from a warehouse in Dolni Brezany, a town just south of Prague. That may be true.

What is undeniably true is that the office address of CalifornianWines in Prague’s Old Town is only a short walk from the Wenceslas Square restaurant where, in late 1968, I enjoyed one of my most memorable meals ever in a city teeming with heavily-armed Russian “tourists.”

But that’s a story for another time.