Trump, Tariffs, and Trade

By Jock O’Connell

Just before Thanksgiving, the editor of a transportation industry publication emailed to ask me how America’s West Coast ports might be affected by the 25% tariffs then President-Elect Trump was threatening to impose on imports from China.

I declined to pursue the squirrel. Parsing the likely effects of the latest of the mercurial Mr. Trump’s frequent and often self-contradicting tweets was not something I was inclined to do. There are more satisfying ways of wasting my time. So I asked the editor to contact me when President Trump had issued more formal positions on tariffs.

Fast forwarding to the days immediately following President Trump’s inauguration, it is still unclear what he has in mind for our trading partners. Apparently, 25% tariffs are to be imposed on all imported goods from our two closest trading partners, Canada and Mexico, on February 1. Unspecified tariffs will also be imposed at some point soon on imports from the European Union. Special duties might also be levied against the goods -- largely pharmaceutical -- we buy from Denmark, because the Danes have been disinclined to hand the deed to Greenland over to Mr. Trump.

Just last weekend, Mr. Trump briefly threatened a 25% tariff on imports from Colombia for refusing to permit repatriation flights from the U.S. As the Central American nation is America’s second largest supplier of unroasted coffee beans, currently accounting for one-fifth of the import trade, coffee drinkers could have expected a price hike in their morning brew. Of the 223,019 metric tons of unroasted coffee bean imported from Colombia in the first eleven months of 2024, 10.8% entered through the Port of Oakland and another 5.2% through the Port of Seattle. Less than two percent arrived through other West Coast ports.

So much for distancing America from its allies.

As for the draconian duties he had promised to charge on Chinese goods, maybe not. Evidently, Mr. Trump is planning a visit to Beijing for a personal chat with Chinese President Xi. For now, a 10% duty on Chinese goods seems to be the administration’s plan.

The White House is justifying the higher tariffs on goods arriving from China, Canada, and Mexico as part of the new administration’s war on fentanyl trafficking. China has been labeled as the principal producer of the drug, while Canada and Mexico have been identified as the principal conduits into the United States.

The two North American allies are also being penalized for running large merchandise trade surpluses with the U.S. Through the first three quarters of 2024, the U.S. had a $55.2 billion merchandise trade deficit with Canada and a $156.2 billion deficit with Mexico. Both deficits were dwarfed by the $267.4 billion imbalance with China. Interestingly, the U.S. has larger trade deficits with Vietnam ($111.6 billion), Ireland ($80.5 billion), Germany ($76.9 billion), Taiwan ($66.1 billion), Japan ($62.8 billion, South Korea ($60.0 billion) than it has with Canada. But then Canada controls that fabled spigot which could supply California with all the water it needs to fight wildfires, irrigate its crops, and keep its golf courses green.

The tariffs to be levied against imports from Mexico and Canada will be hugely disruptive given the broad extent to which key industries in the three nations have integrated their operations during the three decades since the original North American Free Trade Agreement took effect in 1994.

However, there should be little immediate impact on West Coast ports. Only 7.7% of U.S. imports from Canada and Mexico last year were waterborne and less than twelve percent of that amount moved through U.S. West Coast ports. The maritime share of U.S. exports to Canada and Mexico is even smaller, and scarcely any of that is transported through USWC ports.

Eventually, though, West Coast ports could see a bump in imports should the tariffs against our two neighbors remain in place for an extended period of time. Importers can be expected to seek other sources of goods formerly imported from Canada and Mexico. West Coast ports like Port Hueneme and the Port of San Diego would probably see a jump in their existing trades in fresh fruits and vegetables from Central and South America. By then, though, the president’s penchant for tariffs could very well have driven up consumer prices and slowed the nation’s economy to the point that imports of non-essential items would likely shrink.

The infinitely larger concern facing West Coast ports involves the prospect of sharply higher tariffs on imported merchandise from China and the near certainty of Chinese retaliation against U.S. exports. It remains unclear whether Mr. Trump would impose a blanket tariff on all Chinese products or would be more selective in the types of imports to be taxed. Past practices, however, suggest that Beijing would respond more selectively by targeting U.S. agricultural exports and goods produced in congressional districts that voted for Mr. Trump.

While much is still up in the air, some sense of what might happen can be had by examining the statistics on U.S trade with China during the first Trump administration.

Exhibit A displays the volume of U.S. containerized imports from China and Hong Kong that entered the major USWC maritime gateways between January 2017, when Mr. Trump assumed office, through January 2021, when his first term concluded. The numbers in that last year were obviously skewed by the eruption of the global COVID-19 pandemic.

Exhibit B reveals the corresponding trend with respect to containerized export tonnage to China/Hong Kong moving through the chief U.S. Pacific Coast gateways.

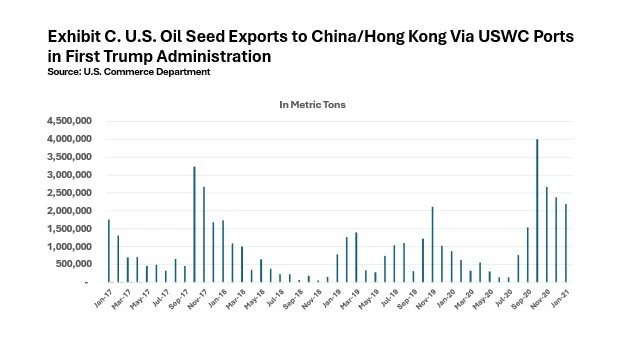

During the first Trump presidency, after the imposition of new tariffs in January 2018 on washing machine and solar panels from China, Beijing famously retaliated that April with higher duties and other import restrictions on American farm exports. (Other restrictions typically included excessive use of phytosanitary inspections or simply slow-walking shipments of perishables through customs inspections.) After a subsequent increase in U.S. duties on steel and aluminum imports, China targeted American soybeans and other oil seeds in July, not only because of their importance to America’s overall agricultural economy but because they are chiefly grown in a swath of red states. The fact that Brazil had begun to emerge as a formidable alternative source meant that China could penalize U.S. farmers without necessarily denying their own import needs. In the year before Mr. Trump took office, oil seeds represented 37.5% of all exports through USWC ports to China and Hong Kong.

Exhibit C shows U.S. shipments of soybeans and other oil seeds to China/Hong Kong through West Coast ports during the first Trump administration.

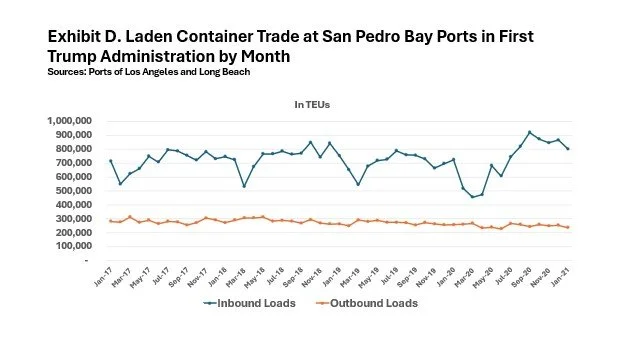

Exhibit D displays the total volume in tonnage of inbound and outbound loaded TEUs at the Ports of Los Angeles and Long Beach during the previous Trump presidency. Outbound trade through San Pedro Bay remained flat through the period, albeit with an evident downward trend. By January 2021, the Ports of LA and Long Beach were exporting 16.1% fewer loaded TEUs than they had four years earlier.

The commentary, views, and opinions expressed by Jock O’Connell are his own and do not reflect the views or positions of the Pacific Merchant Shipping Association. PMSA does not endorse, support, or make any representations regarding the content provided by any third party commentator.